Scan barcode

A review by buddhafish

The Besieged City by Clarice Lispector

2.0

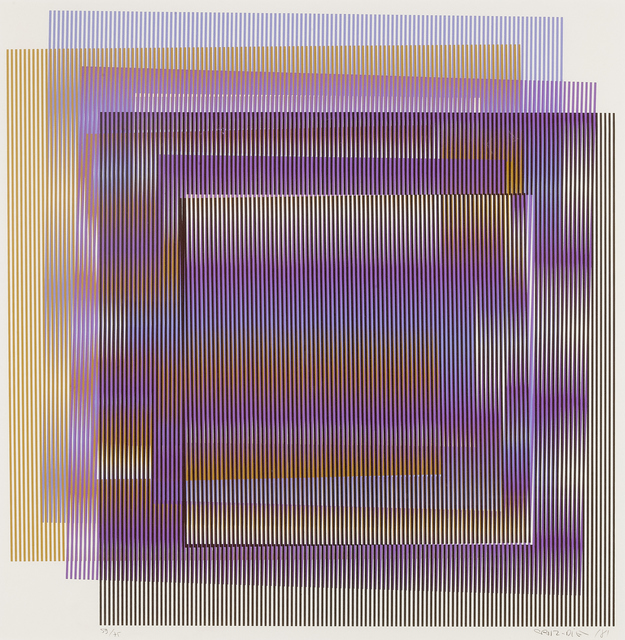

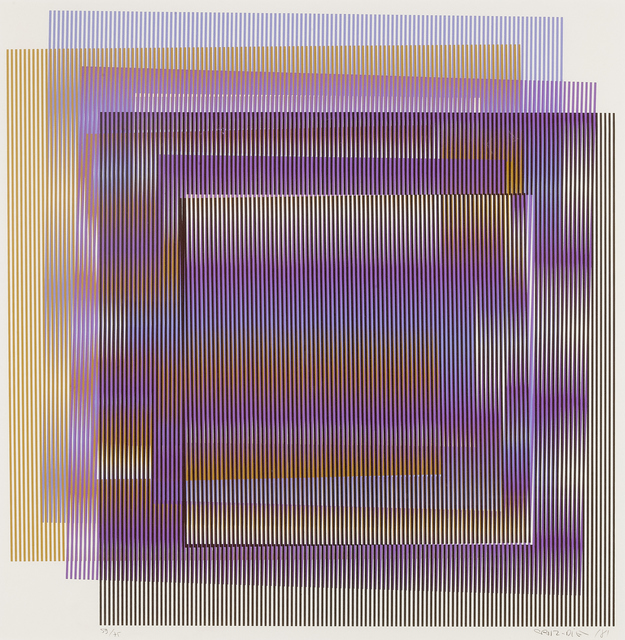

[24th book of 2021. Artist for this review is Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez.]

This is a dense novel. In the beginning I could only manage working my way through a few pages at a time, and extracting any meaning was difficult; it is elusive, almost impenetrable. Throughout the novel certain images reoccur, but namely, the image of horses. They prevail throughout the entire novel, sometimes, even our protagonist is described as stamping her hooves. And though the language is beautiful at times, it felt as if it was too distant, and driving towards nothingness, that left the whole novel feeling slightly cold—as if I was witnessing something very beautiful on another shoreline, with my vision blurred and slightly distorted by ripples of heat.

“1 plate, from Chromointerférence, 1981”—1981

I wrote out some thoughts on an old receipt the other night and after some translation issues (from indecipherable to decipherable) I read it again:

At first I thought there wasn’t enough sunshine to pour into the uncooperative recesses of my brain, but then the sunshine came and instead my brain was blinded; then it was too windy and my thoughts were constantly scattering south; then there was no wind, so my thoughts settled into stillness and stagnated; then it rained and my brain was flooded. In the end I realised it was me, or the book, but not the weather.

A little abstract, but it is an abstract book. At the halfway mark I was idly flipping through the pages until I realised an appendix, which contained a review from the Brazilian critic Temístocles Linhares and then a response from Lispector herself, which she wrote twenty-two year later after happening upon the review.

“Physichromie 2232”—1988

I won’t bother delving into Linhares review, though I will record its final line: And the result is that the work circles around a life and a drama without managing to lend them more than a simulation of a novel.

Lispector’s response is worthy of some reflection. It did change an element of my reading in the second half of the novel. She begins by saying, Your review is pointed and well-done. Further down she writes, What astonishes me—and this is certainly my own fault—is that the higher purposes of my book should escape a critic. Does this mean I couldn’t bring to the fore the book’s intentions? Or were the critic’s eyes clouded for other reasons, not my own? She claims, As for the book’s “intention,” I didn’t believe it was lost, in a critic’s eyes, through the development of the narrative. I still feel that “intention” running through all the pages, in a thread perhaps fragile as I wished, but continuous and all the way to the end. Lispector’s words are more resounding here than in the novel itself, for me: The way of looking gives the appearance to reality. When I say that Lucrécia Neves [the protagonist] constructs the city of São Geraldo and gives it a tradition, this is somehow clear to me. When I say that, at that time of a city being born, each gaze was making new extensions, new realities emerge—this is so clear to me. She talks in this vein, or seeing, of creating, of reality, until the letter’s conclusion:

This is a dense novel. In the beginning I could only manage working my way through a few pages at a time, and extracting any meaning was difficult; it is elusive, almost impenetrable. Throughout the novel certain images reoccur, but namely, the image of horses. They prevail throughout the entire novel, sometimes, even our protagonist is described as stamping her hooves. And though the language is beautiful at times, it felt as if it was too distant, and driving towards nothingness, that left the whole novel feeling slightly cold—as if I was witnessing something very beautiful on another shoreline, with my vision blurred and slightly distorted by ripples of heat.

“1 plate, from Chromointerférence, 1981”—1981

I wrote out some thoughts on an old receipt the other night and after some translation issues (from indecipherable to decipherable) I read it again:

At first I thought there wasn’t enough sunshine to pour into the uncooperative recesses of my brain, but then the sunshine came and instead my brain was blinded; then it was too windy and my thoughts were constantly scattering south; then there was no wind, so my thoughts settled into stillness and stagnated; then it rained and my brain was flooded. In the end I realised it was me, or the book, but not the weather.

A little abstract, but it is an abstract book. At the halfway mark I was idly flipping through the pages until I realised an appendix, which contained a review from the Brazilian critic Temístocles Linhares and then a response from Lispector herself, which she wrote twenty-two year later after happening upon the review.

“Physichromie 2232”—1988

I won’t bother delving into Linhares review, though I will record its final line: And the result is that the work circles around a life and a drama without managing to lend them more than a simulation of a novel.

Lispector’s response is worthy of some reflection. It did change an element of my reading in the second half of the novel. She begins by saying, Your review is pointed and well-done. Further down she writes, What astonishes me—and this is certainly my own fault—is that the higher purposes of my book should escape a critic. Does this mean I couldn’t bring to the fore the book’s intentions? Or were the critic’s eyes clouded for other reasons, not my own? She claims, As for the book’s “intention,” I didn’t believe it was lost, in a critic’s eyes, through the development of the narrative. I still feel that “intention” running through all the pages, in a thread perhaps fragile as I wished, but continuous and all the way to the end. Lispector’s words are more resounding here than in the novel itself, for me: The way of looking gives the appearance to reality. When I say that Lucrécia Neves [the protagonist] constructs the city of São Geraldo and gives it a tradition, this is somehow clear to me. When I say that, at that time of a city being born, each gaze was making new extensions, new realities emerge—this is so clear to me. She talks in this vein, or seeing, of creating, of reality, until the letter’s conclusion:

No, you didn’t “bury” the book, sir: you too “constructed” it. If you’ll excuse the word, like one of the horses of São Geraldo.

Clarice Lispector